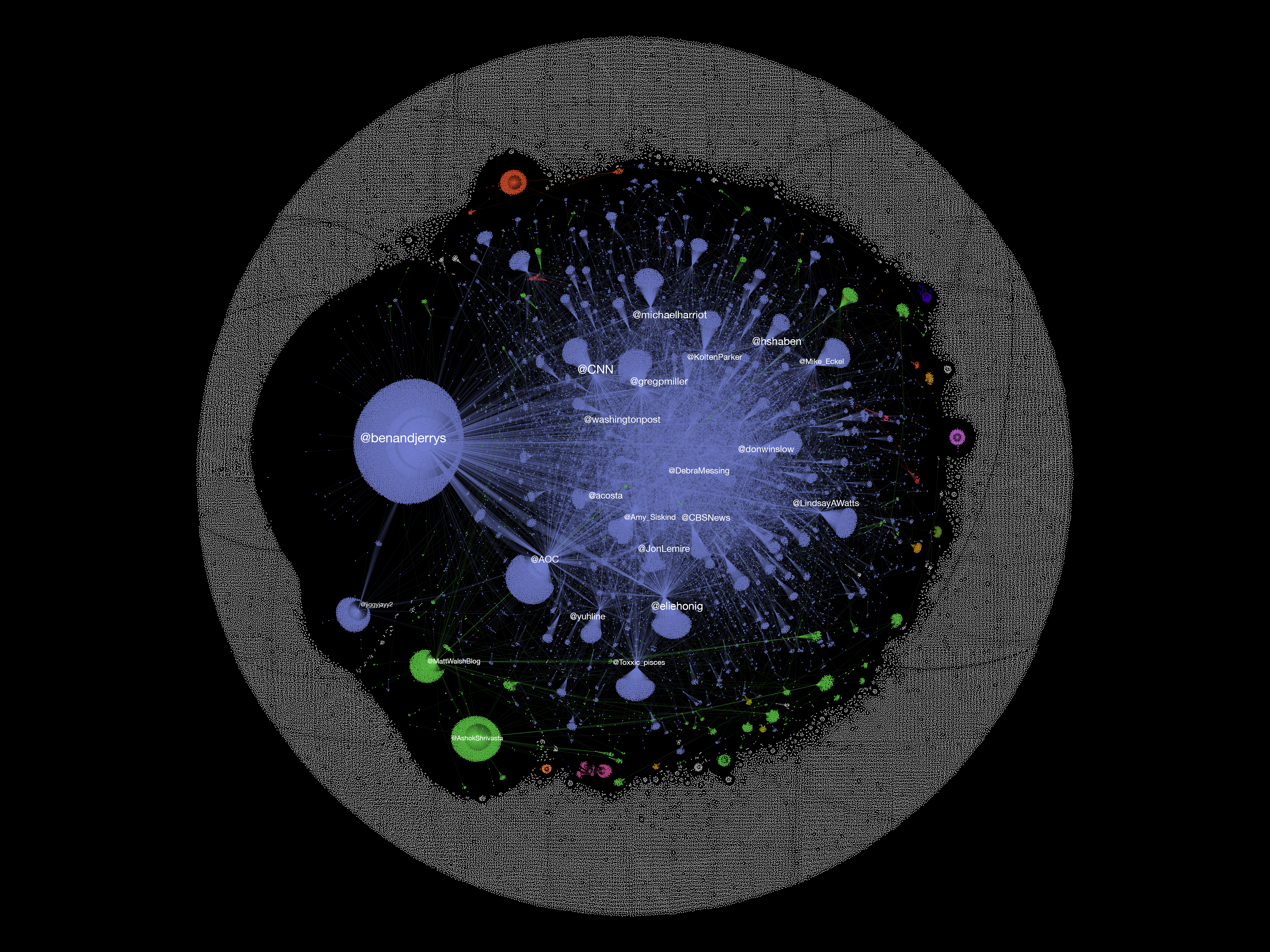

This visualization is a network of the distribution of retweets between Twitter users. In this network, larger nodes indicate that the account was retweeted more frequently by others, and edges represent that two accounts are connected by one retweeting the other. The colors represent clusters, which are grouped according to modularity, or how tightly knit subgroups in the network are.

Overall, the modularity of the network is very low – only .274. This is evident in the way the individual nodes are distributed along the outside of the network. These nodes aren’t connected to anything, meaning they did not retweet any other nodes in the network, or get retweeted. However, there are a few key clusters, represented by different colors.

Most noticeably, the light purple nodes and edges are highly connected in contrast to the rest of the network. These nodes are, for the most part, the most retweeted tweets in the network, and are accounts somewhat related to each other. Many news and politics/advocacy accounts are represented in the purple cluster, including CNN, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, reporter Greg Miller, CBS News, and more. The relatively high clustering of individuals belonging to these groups is unsurprising but interesting to see in the grand scheme of the conversation.

Existing literature confirms this finding: According to the Pew Research Center, 97% of tweets about national politics come from just 10% of users [2]. Before the riots, 72% of tweets mentioning national politics were from users who strongly disapprove of President Trump [2]. These people are interacting the most with others in the network and creating unique tweets that are circulated by individuals similar to themselves. The result is a more closely connected group within the larger network, where highly-connected news and political individuals engage with similar information and disseminate it to large volumes of people.

The node with the highest weight (the most connections), is the Twitter account belonging to Ben and Jerry’s. Their tweet was the most retweeted in the entire network. Interestingly, this node is somewhat far removed spatially from the more politically-inclined (journalistic, political) nodes in the light purple cluster. This suggests that Ben and Jerry’s was for the most part related to other accounts in the network only by virtue of other accounts retweeting their tweet. Ben and Jerry’s was not a large part of the conversation – they were not highly engaged with other accounts – while journalists and politicians were more likely to engage with those in their immediate networks by both retweeting each other and getting retweeted. However, corporate activism was an important part of condemning the riots in the following days [1]. Five days after the riots on January 11th, over forty large corporations committed to reviewing or suspending PAC donations to lawmakers who voted against certifying election results.

Looking at other distinctive and noteworthy clusters in the network, another that stands out is the bright green cluster. This cluster is composed of more personal accounts. These tweets that were somewhat highly retweeted were viral, but not in the cluster that was talking about and retweeting information about the capitol riots the most. These were more likely to be memes, jokes, or other comments less closely tied with precise descriptions of the event. Notably, each bright green cluster is somewhat far away from other bright green clusters, showing that though they are related to each other by the fact that they attract fringe groups, those fringe groups may be minimally related to each other otherwise.

Another interesting, small cluster, is located at the top left corner of the visualization and is bright orange. All the nodes in this small cluster retweeted a tweet by user @PowerofTakaya. This tweet is isolated because it’s not connected to the Capitol riots at all – it’s a tweet about a video game in Japanese. The user happened to use the word “riot” on January 8th, so though they were not discussing the Capitol riot, their tweet was included in the dataset anyway.

Surrounding these more highly clustered groups are thousands of unconnected nodes. These nodes illustrate the many people contributing to the discussion of the riot with tweets that never travel throughout the network. This is a very large part of the network, illustrating how ‘virality’ on platforms like Twitter is very rare. Only 34 users were retweeted over 1,000 times in our corpus. That leaves out another 269,156 users that had only minuscule contributions to the conversation at large.

Those 34 users, the number of retweets each got, their account types, and the average ideology score per category are as follows:

From the visualizations above, we can see that just a handful of users saw true viral success with their tweets – one of those users being Ben and Jerry’s. Ben and Jerry’s is an outlier amongst the top 34 most-retweeted users, however, being the only corporate entity not involved with producing news content. We can see that of the top 34 most retweeted users, we can see that the large majority are news organizations or reporters. The other categories are all barely represented in comparison, the next-most represented categories being politics, celebrity, and comedy, with only three users in each category.

This may also reveal the nature of the information people wanted and felt was important during the days after the Capitol riot. For those who weren’t at the Capitol that day, it was difficult to understand what exactly happened. In the days following, reporters were able to attain more and more information shedding light on the events of the day and related issues like QAnon, the police presence at the riot, and the planning of the riot, among other things. People may have been interested in finding that information and spreading it.

Though the above may partially explain the flow of information about this set of events, it’s imperative that we also acknowledge the rest of the accounts in the light purple part of the network. The largest nodes in this network are news and politics accounts – accounts that belong to people most interested in the pursuit and spreading of information. Twitter already skews towards overrepresenting those who choose to use their voice on it versus those that merely lurk, and this may also be part of what we’re seeing here. Reporters have largely turned to live-tweeting as a form of reporting since the rise of Twitter as a fast and effective way to spread information to large audiences. They are supported by other reporters whose job it is to spread that information as well, explaining why that part of the network, in particular, maybe so densely connected.

It’s evident that the structure of this network largely favors news information, but at the same time, it’s notable that this news information isn’t being engaged with by a large number of users. That does not mean that those tweets aren’t reaching those users at all (we don’t have data about likes or impressions), but it does show how key players in the media do strongly influence conversations about political events on the web.

Given that news accounts tend to skew more neutral ideologically, or even more conservative-leaning in comparison to Twitter users as a whole, it’s interesting to see that these accounts are dominating this dataset. On average, accounts in the news category for the top 34 retweeted users are more conservative than those in most other categories represented. Overall, however, there are more tweets/users categorized as leaning liberal, though those tweets are not necessarily the largest in the network. Echo chambers, when users are exposed to mostly opinions that share their own views, are increasingly forming on social media [3]. On Twitter this phenomenon is rampant, as most users are exposed to political opinions that are similar to theirs. This is in part due to Twitter being a microblogging directed network and accounts a user follows are more likely to engage and endorse political tweets with similar viewpoints [3].

This visualization shows the average partisanship score per category represented in the top 34 most-retweeted users. Given that news accounts tend to skew more neutral, or even more conservative-leaning in comparison to Twitter users as a whole, it’s interesting to see that these accounts are dominating this dataset. On average, accounts in the news category for the top 34 retweeted users are more conservative than those in most other categories represented. Overall, however, there are more tweets/users categorized as leaning liberal in the entire corpus, though those tweets are not necessarily the largest in the network.

This does not mean that mostly neutral/slightly right-leaning information is what’s spreading around the network in the context of the Capitol riots. It simply illustrates that these people are the key nodes in the network – they dictate the conversation to a certain extent, but that does not limit other users to reacting to the information presented neutrally. In the context of the Capitol riots, it makes sense that the foundation of conversation is coming from these sources – new information coming out after the riots were fodder for intrigue and opinion-sharing.

In contrast to those more neutral/right-leaning users that are central in the network, we also see highly political posters and tweets from users like Ben and Jerry’s and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. For future research, it would be interesting to look at tweets further after the Capitol riots to see how the central nodes change over time and react to there being less immediate news.